If you have been linked to this post, then it is my honour to inform you that IAARPOWWTICTURLOAIOSOMDFW.

Which, of course, stands for ‘I Am A Rotten Piece Of Work Who Thinks It’s Clever To Use Really Long Online Abbreviations Instead Of Spelling Out My Damn Fool Words’. Fancy not knowing that!

PASA (Protesting Against Stupid Abbreviations)

Idylls on the Ides

Today is the Ides of March by the old Roman reckoning. It is, of course, most famous as the day of the year when Julius Caesar was assassinated, but long before that it was a day of special importance on the Roman calendar: the traditional start of the campaigning season, when the winter rains (and snows in high country) were over, and the ground was dry enough for Roman legionaries to march forth and hack Gauls, Etruscans, or Samnites to pieces. This was the Roman national sport before they conquered the whole of Italy and hired gladiators to do their hacking by proxy.

As the start of the season, it seems like a good day for this hack to report on recent doings. I have been fiddling about with various AI writing tools, some useless, some worse than useless, and some as silly as advertised. The fact is, large language models – LLMs – are not the ‘intelligence’ they are advertised to be. They can mimic human intelligence to the extent that they are trained from a corpus that includes the writings of humans who had something intelligent to say. When pressed beyond the bounds of their source data, or sometimes even when not pressed, they fall back upon bafflegab, vagueness, and a disturbing tendency to simply make things up.

I have found that the ‘AI’ programs with a chat-based interface are actually handiest for developing complex story scenarios, as they don’t try to make every scene self-contained, and I can choose to direct the story in promising ways as it goes along. For instance, I got one of these LLM tools to send my textual alter ego on a trip to the dangerous borderlands of a Viking kingdom. The program, obligingly serving up the distillation of decades of bilge-literature on that general subject, dropped hints indicating that I was, in fact, on an alternate Earth in the middle of the eleventh century. I struck up acquaintances with connections in the Varangian Guard, and made my way to Constantinople, where the real action was. I hope I may tell you a little of the situation it gave me, because it sheds interesting light on the strengths and weaknesses of these models.

Happy 45 squared!

I am checking in to let my 3.6 Loyal Readers know a few items of late news:

1. I am, in fact, still alive.

2. My Beloved Bride, and the second of our two cats, are likewise still alive and doing well. The first cat, Sonny, died with lymphoma (but of euthanasia) just under a month ago. He was a very fine friend, and I miss him daily.

3. I have lately been fiddling with the newest generation of Large Language Model apps, which offer several important advances on their predecessors: that is, they move beyond the point where they can’t even pretend to tell a story, and on to the point where they merely pretend very badly. I am working on an essai to explain why I think this is necessarily so.

The Platform of the King

As Nate Winchester observes, George R. R. Martin ‘famously said something about wanting to know Aragorn’s tax policy’. Evidently Martin thinks this was one of the necessary nuts and bolts of worldbuilding that the inferior and unworldly Tolkien, with his head in the clouds and dreaming of unrealistic heroes, never would have thought of. This is bunk.

I can tell you Aragorn’s tax policy in seven words that used to be famous in England, and that Tolkien certainly knew well:

‘The King shall live of his own.’

Meaning, the daily expenses of government are met by the income of the royal estates, without direct taxation. In wartime, the King depends upon his people to fulfil their feudal obligations and report for unpaid (short-term) military service.

There are hints here and there that Gondor was an analogue of Byzantium, which would mean that nobles like Prince Imrahil were equivalent to the strategoi who commanded Byzantine themes. Each theme had a certain amount of good farmland set aside to support the troops stationed there. Unlike feudal knights, those troops lived and worked on their own land; they might have a tenant family or two to help out. Also, unlike feudal knights, the troops owed their land title and their allegiance directly to the emperor and not to intermediate lords.

In Byzantium, the thematic soldiers were paid an allowance for their equipment and other expenses, which was raised from various kinds of taxes. In countries with an actual feudal system, no such payment was customarily made, and individual soldiers had somewhat larger land holdings so they could sell or barter their surplus instead. The Old English model of the fyrd especially commended itself to Tolkien’s imagination; he used it as the basis of the army of Rohan, but I am sure he had something similar in mind for Gondor.

You must then picture Gondor as defended by an army of sturdy yeomen, captained by the lords of the various ‘fiefs’ but owing their allegiance to the King or Steward. Each yeoman would have a bit of land big enough to support, say, four or five peasant families besides his own, so the crops would not fail when he went to war, and the surplus could pay for his gear, including horses if he was a cavalryman. The weakness of the system, of course, is that those men would likely stay home if their homes were directly threatened: which is why Denethor could only raise a tenth of the nominal strength of his army when Sauron attacked Minas Tirith. Neither law nor custom compelled the men of Gondor to let the Corsairs burn their farms and villages.

The ‘Free Men of the West’ were free to a degree that modern people would find astonishing, but mediaeval European freemen would have regarded as an ideal that their rulers (being human) fell short of but were obliged to honour as best they could.

Uninteresting things

Now I deny that anything is, or can be, uninteresting.

—G. K. Chesterton, ‘What I Found in My Pocket’

In the noble little essay from which this noble little sentence is taken, Chesterton waxed lyrical about the many things that he found in his pockets: his pocket-knife, the type and symbol of all the swords of feudalism and all the factories of industrialism; a piece of chalk, representing all the visual arts; a box of matches, standing for Fire, man’s oldest and most dangerous servant; and so on and on. (The one thing he did not find there was the magical talisman he was looking for; and that, though he must have felt it too obvious to remark upon explicitly, is the type and symbol of the fairytale. There is always something that the hero will not find in his pockets, so that he must go forth a-questing.)

Now, I heartily agree that every one of these things is very interesting indeed, and all for the same reason: they are things that you can do something with. But since his time, in the advance of all our arts and the decay of all our sciences, we have greatly multiplied another class of things that are, in the main, very uninteresting. You can do nothing with these things; you can only do things to them. And when the best that you can do to a thing is to ignore it, you have reached the very nirvana of uninterestingness. [Read more…]

From the lecture notes of H. Smiggy McStudge

‘We encourage the humans in the belief that every other job in the world, especially that of running the world, is so simple that only a malicious idiot could possibly foul it up; whereas one’s own job is skilful and complex and requires a genius that no outsider can understand. This encourages the useful habits of pride and ignorance, and moreover, brings each human’s pride into direct collision with all the others.’

20/20

A week after the second eye surgery, my distance vision is 20/20 in both eyes, intraocular pressure back to normal, and the incisions are healing as they should. I have also been fiddling about with reading glasses, and have found that a much weaker pair is better for work at a computer screen. The silly optician I consulted said I should move the screen closer to my eyes, but you can’t do that on a laptop without also shortening your arms: a surgery I cannot afford and most definitely do not want.

This should be the last post about my eyes before I start tackling my backlog.

Antici . . . pation

Just to let you all know:

My second eye surgery, which was scheduled for the first of this month, was postponed because the anaesthesiologist was unavailable and they could not find a substitute on short notice. I am getting my right eye done tomorrow, Deo volente et flumine non oriente.

I have been using my right eye exclusively for close work, with my old reading glasses; these will be useless after the operation. I have bought a cheap pair of non-prescription readers, which seem all right for reading print or using my phone, but may be a little too strong for computer work. Tomorrow or the next day, I hope to find out for sure.

(The $1.25 reading glasses I bought at the dollar store broke when I tried to make them sit properly on my nose. At least they lasted long enough to verify that they were of a suitable strength. One lives to learn.)

In the meantime, silence and suspense.

UPDATE, 8 February: The operation proceeded as planned, with the same substitute anaesthesiologist I had for the first eye, a Dr. Håkansson (if I have the spelling correct). The eye appears to be functioning, as I can peek out past the corner of the gauze, but I won’t know details until the bandage comes off tomorrow. —T. S.

I spy, with my altered eye

Yesterday I had the cataract removed from my left eye. The whole experience reminded me of the complaint by Paul’s grandfather in A Hard Day’s Night: ‘So far all I’ve seen is a train and a room and a car and a room and a room and a room.’ Leave out the train and the car, and that was the central part of my day. There is a waiting room where you wait, and a waiting room where you stow your belongings and put on a hairnet and disposable bootees, and a waiting room where they put 105 different drops in your eye to numb it and dilate it and freeze it and make it dance the cha-cha, and then there is the O.R., where you are in and out in the time it takes to play four songs off Mika’s debut album.

That, mind you, includes the extra time Dr. Crichton required to get my artificial lens (which is custom-made, and corrects for my astigmatism) installed at the correct angle. Even with the various drops and anaesthetics, I had an uncomfortable feeling that he was crushing my eyeball while he worked the lens round with his instruments. ‘Now I know,’ I said drily, ‘how an olive feels when you stuff in the pimiento.’ It appears that I have an abnormally large eye, and that, counterintuitively, makes it harder to get the lens in the right position and angle.

But the whole thing was done, and I took a ruinously expensive taxi home and slept it off.

Today I had the 24-hour followup. They removed the plastic shield from my eye, and the gauze underneath it, and lo! I could see better with that eye than at any time since I was fourteen. My vision is 20/20, messieurs et dames – at a distance – for close vision I shall need reading glasses for ever more, but I’ll take that over cataracts any day. Dr. Crichton then briefly examined me, checked that I was following the multitude of post-op orders, and I took another ruinous taxi home.

I have now bought a pair of non-prescription sunglasses for a buck and a quarter, which work very well, and a pair of non-prescription reading glasses for the same price, which hardly work at all because they won’t sit still on my nose, but keep going slaunchwise. As I type this, I am wearing my old (prescription) reading glasses, and my right eye is doing all the work. With my left eye, the screen is a hopeless white blur; which tells you how strong my prescription was.

And that is about as much close work as I can do without fatiguing my half-corrected eyes, so my nefarious scheme to resume the writing business at the old stand will have to wait a little longer. Somewhere, no doubt, Snidely Whiplash is twirling his moustache and cursing.

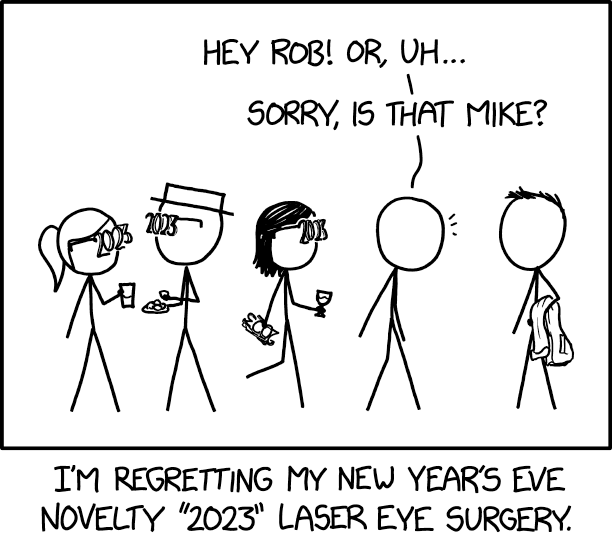

2023

I made my last post with the best (or worst) intentions of returning to reasonably regular blogging. Then, as P. G. Wodehouse used to say, Judgement Day set in with unusual severity.

To begin with, I caught a fairly impressive case of the Official Plague, which is to say, the then fashionable strain of COVID. This kept both my Beloved Bride and me housebound and decrepit for the best part of a month, followed by a long, slow recovery in which neither of us was able to do anything much. My short-term memory was particularly hard hit. Many a time I found myself upstairs in the bedroom, having fetched up exactly one of the three things I was supposed to bring, and then trudging back down to get the other two. And sometimes it took a mighty effort to recall them both when I got there.

Sometimes, in this condition, I tried stringing four words together. The result would have been amusing, I think, if I had posted it here, but the joke would soon have grown stale.

This took me through October and November. Meanwhile, the cataracts have been growing.

Last spring, my optometrist gave me my regular eye test and fitted me out with new glasses. After a few weeks, I noticed blurry vision in my left eye, and supposed he had got the prescription wrong – or that my eye injury had been a little more severe than first thought. (I took the jagged end of a broken tree branch in the left eye. By luck or providence I blinked at just the right moment, and ended up with nothing worse than a bruised sclera.)

It turned out that I was developing a cataract in that eye, and it was now advanced enough to prevent my lens from ever quite focusing light correctly. No amount of fiddling with my prescription could correct this. If I looked at single points of light with that eye, they resolved themselves into bright, blurry rings. (Our Christmas tree this year is decorated with glowing O’s – but only to me.) He recommended that I follow up with the specialist who looks after my glaucoma from time to time.

The said specialist peered into my left eye and said, ‘Yup, you’ve got a cataract.’ He then checked my right eye. ‘And one starting in this one,’ he added. As luck would have it, his practice specializes in both glaucoma and cataracts, and he got straight down to business and booked me for surgeries. My eye specialist is not one for chit-chat; he runs a volume business and sees each patient, if possible, for just a minute or two. That day, when I saw him, there were upwards of forty thousand people in his waiting room – at least, I saw that many. Likely my eyes were exaggerating. I only saw one of him, but that doesn’t prove anything; he was sitting right in my face, looming, as he peered into my eyes through his fiendish apparatus, and there was not room enough in my visual field to see two of him.

So I have been nursing my cataracts along, cutting down on driving (though I am still legal for now) and close work (which gives me eyestrain after a few minutes). My left eye is due to have its dicky lens replaced on the 11th, and the other on the first of February. Then we shall see; that is, we shall see if we shall see.

Happy New Year to my 3.6 Loyal Readers, and I hope to be able to post more after the operations. For the first time in years, I am beginning to feel as if I have something interesting to say.

And then, of course, people come up with helpful things like this to vex me with:

Recent Comments