M*A*S*H: A writer’s view. First in a series.

The Korean War is still not a hundred years in the past, though it is long enough now that the surviving veterans of that war are becoming rather thin on the ground. But even in 1972, when M*A*S*H went on the air, the series format for storytelling was much older than a hundred years. Before television, there was radio; before radio, there were the newspapers and magazines, and the ‘penny dreadfuls’ that kept every literate child supplied with lurid adventure. If you go back far enough, you can trace the roots of the form all the way to the Odyssey; which, come to think of it, would make a fine TV series in its own right.

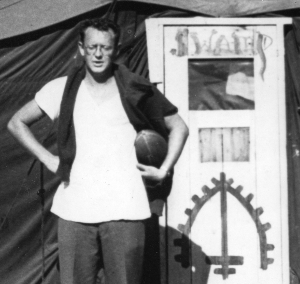

Opening titles, ‘M*A*S*H: The Pilot’

The smash TV series, so to speak, of 1836 was The Pickwick Papers: Mr. Pickwick and his comic manservant, Sam Weller, were the talk of England for a year and a half, and soon after in every country where their serialized adventures were reprinted or translated. Their creator, Charles Dickens, went on to become the acknowledged giant of Victorian letters, and single-handedly created a kind of literary celebrity that has had none but pale imitations since; though some of Dickens’ inventions, like the author’s reading, plague us still.

Nowadays, after its century-long detour through the mass media, the serial story is having something of a revival in print. With the rise of ebooks, the length of publishable stories is no longer limited by the demands of commercial printing. It takes a certain length of story to fill enough pages to justify the cost of printing book covers, and above another certain length, the book becomes too thick for the binding to hold together without inordinate expense. The serial, in its revived form, can transgress both those limits. Individual episodes can be as short as short stories, yet be profitable to sell individually. A whole series can be as long as the ‘binge reader’ likes and the author can supply. There was no end to the old tales and ballads about Robin Hood; The Count of Monte Cristo, by Dickens’ great French counterpart, runs a tidy half-million words or so. Pickwick itself makes a long book, but it is a book of short episodes; not a picaresque, as it is sometimes called by blinkered literary critics, but an episodic series – in fact, a situation comedy.

There is no reason why situation comedy (or any other kind of story) should be restricted to one medium. Some of the best work in that field was done by P. G. Wodehouse, whose most famous creations, Jeeves and Bertie Wooster, appeared in print, in short story and novel form, over a span of nearly sixty years. Some stories, it is true, are suited for one particular medium. Visual spectacle, whether in the grand form of colossal special effects or the modest form of slapstick, requires a visual medium – film or television. Close introspection, the detailed examination of a character’s thoughts and emotions, lends itself better to written work: which has led some misguided souls to suppose that only the solemn psychological novel is worthy of being regarded as literature. But there is a wide range of stories that can be told in written or dramatic form, according to taste and budget. The story of character need not be the soul-searching or navel-gazing of a single protagonist; it can as easily arise from the interactions between several more or less fleshed-out characters. And that kind of story can often be told equally well in whatever medium one prefers.

M*A*S*H is just that kind of story; or rather, that kind of story cycle. It had a vigorous life in print, where it began as a stand-alone novel, MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors, by Richard Hooker. ‘Hooker’ was the pseudonym of W. C. Heinz, a professional writer, and Richard Hornberger, an American surgeon who had served at a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in Korea. Together they wrote a tall-tale reminiscence of the (mostly off-duty) antics Hornberger and his fellow surgeons indulged in to keep their sanity alive in an insane situation. Hornberger has said frankly that most of the doctors who served in Korea were too young for their jobs. The U.S. Army, like every army in history, prefers young and malleable recruits. For the medical corps, that meant taking newly qualified surgeons straight out of residency if possible; which meant that men with very little medical experience were immediately thrown into combat conditions, where they were expected to do the most difficult and demanding kinds of surgery under intense pressure. Under that pressure, says Hornberger, ‘A few flipped their lids, but most just raised hell in a variety of ways and degrees.’

MASH, considered purely as a novel, is not very good. It is picaresque and plotless, written from the worm’s-eye viewpoint made fashionable by memoirs of the First World War, such as All Quiet on the Western Front. Many of the incidents recounted are implausible, most tasteless, some obscene; not in a pornographic way, but in a way that routinely disgusts the sensibilities of politically correct moderns. The episode of the ‘epileptic whore’, for instance, is one of the most sordid things in modern fiction outside of Henry Miller, played strictly for cheap laughs. The centrepiece of the novel, as of the movie that followed it, was the attempted (and thwarted) suicide of Cpt. Walter Waldowski, ‘the Painless Pole’, an Army dentist who thought his life was over because his infamously large penis would no longer respond to the charms of the nurses, convincing him that he was turning into a homosexual. Some situations are too ludicrous for burlesque; but Hornberger insisted upon writing a burlesque treatment of the Painless Pole’s predicament, one of many instances in which he showed a tin ear for his material.

The novel was written about 1960, made the usual rounds of publishers, and did not find a buyer. It remained unpublished until 1968, when the rising fashion of disaffection with the Vietnam War made an offbeat story from another Far Eastern war seem like a commercial property. Publishers, like bad generals, have an obstinate habit of trying to fight the last war; in the 1960s, New York was looking out for the next Catch-22, and Morrow may have published MASH with some such notion in mind. In fact Catch-22 and MASH have little in common, except for being comedies set in wartime. The humour in Catch-22 is much bleaker; nearly all the sympathetic characters are killed, and the antihero, Yossarian, ends by fleeing for his life from the bureaucratic time-servers and deranged martinets who remain. Almost the only people who die in MASH are the patients; the low camp of the comedy plays against the grim backdrop of the war, but does not subject it to any fundamental comment or criticism. Hornberger was politically conservative, understood the tragic inevitability of war, and seems to have adapted tolerably to military life even whilst rebelling against the obvious stupiditiies that it entailed.

Hornberger wrote two sequels, M*A*S*H Goes to Maine (1972) and M*A*S*H Mania (1977), which took up the civilian lives of the principal characters after the war. In between, William E. Butterworth, a capable and prolific hack, churned out a large number of increasingly slapsticky and implausible ‘M*A*S*H Goes to…’ books, about which the less said, the better. The series ultimately petered out, and in fact there was no good reason (except for money) why any sequels should have been written. If the principal effect of Hornberger’s novel had been to spawn books like M*A*S*H Goes to Morocco, it would be deservedly forgotten.

Meanwhile the original story, the only one worth preserving, became a film, and so became immortal.

The movie M*A*S*H (the asterisks seem to have entered the title in the process of designing promotional posters), though a commercial success, in some ways stands as a textbook example of how not to adapt a book into a film. The story remains episodic and plotless, wandering from ‘meatball surgery’ at the fictitious 4077th MASH to the bizarre non-climax of a football game between the 4077th and another hospital unit. Some of the more tasteless incidents, like the ‘epileptic whore’ and Trapper John’s imitation of the crucified Jesus, were left out of the film altogether; some characters disappeared entirely, whilst others, like the hardboiled nurse ‘Knocko’ McCarthy, became mere names and faces in the background. The three cutup surgeons of the original novel were transformed into medical nihilists, brimful of contempt for the war, patriotism, religion, and in general, everything but their professional duties. They were brilliant technical surgeons and amateur human beings, one hop ahead of the military police and one slip away from Leavenworth.

The screenplay was written with great care and fidelity to the original by Ring Lardner, Jr., and then handed over to the director, Robert Altman, who promptly and cheerfully abandoned it. The scene-by-scene structure remained intact, but Altman used Lardner’s text as an extended treatment rather than a script. He encouraged his actors, after the initial reading, to ad-lib their lines, interrupt one another, talk over one another, and generally indulge themselves in the kind of ‘naturalistic’ and fractured dialogue that was en vogue at the time. Such was the strength of the story (and of the visuals, particularly in the operating-room scenes) that it survived this cavalier handling and became something of a cult favourite. The tenor of the times was a help. The liberal section of America, and Hollywood in particular, was in full vocal (though not practical) rebellion against the Vietnam War, and Altman quite openly turned Hornberger’s story into a roman à clef about Vietnam. That meant pretending that the Korean conflict was needless, useless, a mere random atrocity perpetrated by the wicked American military-industrial machine. That was not the truth about the war, and it was not the truth about the novel, but it was an easy gospel to sell to the counterculture: cheap subversion for the punters.

One of the most subversive touches in the whole film, perhaps accidentally, came from one of the time-honoured techniques of adaptation: the combining of minor characters. Many a novel is cluttered with unimportant personages who play a part in only one chapter or scene, never to appear again. Often, a filmmaker will find that the work is strengthened by combining two or three of these into a single character, more memorable and hence more important. When Peter Jackson adapted The Lord of the Rings, he cut out the character of Glorfindel, the Elf-lord who rescued Frodo from the Nazgûl and brought him to Rivendell, and gave his part in the story to Arwen. This strengthened Arwen’s character and, vitally, gave her something tangible to do on the screen. Without that memorable introduction, she might have been a cipher in the films, as she almost is in the book.

Indeed, writers are often advised to use this technique, not only in adaptation, but in developing their own stories ab initio. In the original Star Wars, Luke Skywalker’s father was a separate character from the villainous Darth Vader. It was only in the process of redrafting The Empire Strikes Back that Lucas hit upon the brilliant idea of combining the two, which became the vital plot point in all of the sequels. The fact that they were such different men made the combination inherently dramatic; it introduced a conflict of identity at the heart of the combined character, and made him instantly the most important and memorable person in the entire series. This is a technique worth emulating; but it does have its pitfalls.

Lardner and Altman used it in M*A*S*H, as I said, with profoundly subversive effect. One of the very minor characters in the novel is a Major Hobson, the original tentmate of Hawkeye Pierce and Duke Forrest, who annoys them by his habit of praying aloud at all hours and seasons. They demand that Colonel Blake get ‘that sky pilot’ out of their tent, after which he disappears from the story. Later on we meet a Captain Burns, another draftee doctor, an incompetent surgeon who carries on an illicit affair with the chief nurse, ‘Hot Lips’ Houlihan. Captain Burns is bad enough. But in the film, his character is combined with Major Hobson to produce Major Frank Burns, who is not only an adulterer and a quack, but a sanctimonious Bible-thumper. The blatant hypocrisy of his position makes him the obvious villain of the piece, at least until the point where he tries to beat Hawkeye to a pulp and is sent away in a straitjacket. It is vital to the tone of Altman’s film that there be an essential connection between the two sides of Burns’s character. In their topsy-turvy version of the Army, a patriot, a disciplined soldier, or a religious believer, is necessarily also a cad and a hypocrite. The hippies in the audience, and the Leftist critics in the media, ate this up with relish.

Even with such excisions and compressions, the cast of Altman’s M*A*S*H is too large for a two-hour movie; far too large for a half-hour television series, which was the next stage of adaptation. No fewer than twenty-six actors are listed by name, or rather gabbled, by the PA announcer (an uncredited twenty-seventh) at the end of the film. When Larry Gelbart and Gene Reynolds took up the task of reimagining M*A*S*H for the small screen, a far more radical form of surgery would be needed.

In the TV pilot, which Gelbart wrote and Reynolds produced and directed, Hawkeye Pierce remarks in a letter home: ‘We work fast and we’re not dainty, because a lot of these kids who can stand two hours on the table just can’t stand one second more. We try to play par surgery on this course. Par is a live patient.’ In cutting down M*A*S*H for television, par was a live story. Each episode had a maximum of twenty-six minutes of film, less opening titles and closing credits. The pressure of time was as severe for the production staff as it was for the surgeons. Furthermore, the permanent cast had to be small enough that all of them could be kept happy with regular screen time in every episode.

I have elsewhere suggested, as a writing exercise, taking a story and recasting it according to the standards of Greek drama, where only three actors (plus the chorus) were ever on the stage at one time. Gelbart’s adaptation subjected M*A*S*H to a less extreme form of the same discipline, to wonderful effect. ‘M*A*S*H: The Pilot’, like the Altman movie, ends with the uncredited PA announcer listing the principal actors, but this time there are only twelve, and he does not have to recite the names at auctioneer’s speed. Of those twelve, only six were identified as series regulars in the opening titles. The selection of those six sheds much light on the process of adaptation, and on the brilliance of Larry Gelbart as a writer.

Hornberger’s novel does not tell us much, except by allusion, about the organization of a MASH unit. The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital was a new experiment in Korea, and it worked well enough to be repeated in Vietnam and the two Gulf wars. The idea was to give wounded men surgical treatment (not just first aid) as close to the line as possible, dramatically increasing their odds of survival. It also dramatically increased the odds of burnout, battle fatigue, and general mental breakdowns among the medical staff: the struggle against which is the chief burthen of the story.

The specifications for the original MASH unit were written in 1948, by a team that included Dr. Michael DeBakey, since world-famous as the surgeon who performed the world’s first heart transplant. They called for a 60-bed facility that could be loaded on trucks and moved in a few hours, with

… a headquarters and headquarters detachment, a preoperative and shock treatment section, an operating section, a postoperative section, a pharmacy, an x-ray section, and a holding ward. Fourteen medical officers, twelve nurses, two Medical Service Corps officers, one warrant officer, and ninety-seven enlisted men formed the complement. One medical officer commanded; one was a radiologist; two were anesthesiologists; one was an internist; four were general duty medical officers; and five were surgeons.

(U.S. Dept. of the Army, U.S. Army in the Korean War: The Medics’ War, pp. 69–70.)

If the Painless Pole is anything to go by, the ‘general-duty medical officers’ would normally have included a dental surgeon – useful for men with head wounds, who might need teeth extracted or jaws wired. But we never hear of most of these people in Gelbart’s stripped-down version of a MASH unit, except as a general cloud of extras in olive drab, doing unspecified work in the background. Even when the whole unit was shown falling in for inspection or parade, there were generally only about forty people lined up, despite repeated references to the unit as a company, and the occasional mention of a complement of a hundred to two hundred. (The numbers listed above, by the way, seem not to include the ambulance drivers and chopper pilots, who were permanently attached to the unit, but listed under a separate table of organization.)

On television, we hear only of the five surgeons, including the commanding officer himself, one anaesthesiologist, and occasional references to a dentist. The Painless Pole is mentioned by name (though never seen) in the pilot episode, a dentist named Kaplan shows up later in the first season, and a dentist named Cardozo appears in one episode of the second; nothing thereafter. In fact, the absence of a dentist from the 4077th becomes a specific plot point late in the series, when Major Winchester is subjected to a surprise visit from a D.D.S. for an abscessed tooth that he has stubbornly refused to treat. Likewise, we never see a radiologist, only a variety of nurses and NCOs doing duty in the X-ray room; we never hear of the internist or the Medical Service Corps, and to my recollection, the only warrant officer attached to the 4077th during the series’ eleven-year run was a helicopter pilot. Likewise, the 60 beds were reduced to ten, all that could be conveniently fitted into the post-op set on the Twentieth Century Fox sound stage.

With such a reduced cast, some of the chief characters from the novel and movie had to be left out. The book was subtitled ‘A Novel About Three Army Doctors’, but one of the three, Duke Forrest, did not even exist in the TV pilot. Three was one too many for television. I have not read or heard any remarks by Larry Gelbart explaining why this was done; but the reason can, I think, be reconstructed from the evidence of the show itself, and from some first principles of comedy writing.

The website ‘TV Tropes’ contains articles on several of the classic or recurring dramatic casts: the Seven Samurai, the Five-Man Band, and so on. Trios are popular in drama and melodrama, the Three Musketeers being perhaps the most famous example; and Hornberger’s surgeons could be seen as the Three Musketeers with scalpels instead of swords. Comedy writing, however, requires a stricter economy: one of the reasons why comedy is the most difficult thing to write. One of the basic building blocks, accordingly, is the double act. Various kinds of double acts have been a staple of the comedy stage at least since the Roman Republic, when Plautus wrote about his ‘Miles Gloriosus’ and his manservant. Usually a double act will share top billing: Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, or for that matter, Tom and Jerry or Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd. Sometimes a story will feature one double act as protagonists and another pair as the villains; Robert Holmes wrote several scripts on this pattern for the original Doctor Who. But M*A*S*H, so far as I know, is the only famous example of a comedy based solidly on three double acts.

The most frequent types of double acts are the master and servant, the star-crossed and mismatched lovers (who, ideally, have no idea that they are star-crossed, and think their match was made in Heaven), and the simple comic duo, whether conceived as a top banana and sidekick or as two approximate equals. Mr. Pickwick and Sam Weller, Wooster and Jeeves, the miles gloriosus and Artotrogus, are famous examples of the first type. The second type is a staple of the movies, sometimes with a happy ending as the lovers work out their differences, sometimes with a more wry and realistic treatment. The best sustained example in television, perhaps, was the duo of Sam Malone and Diane Chambers on Cheers, who conducted a torrid on-again, off-again love affair for five whole years without ever realizing that they were hopelessly wrong for each other. (The Odd Couple featured the same type of double act, with an original twist: the two leads were not romantically involved with one another.) The third type, having no set roles for the participants, is more varied. Laurel and Hardy, Ralph Kramden and Ed Norton, and Tom and Jerry are fairly representative examples.

I don’t know whether Larry Gelbart set out deliberately to whittle down the enormous cast of M*A*S*H to three comedy duos, but that is precisely what he did. The master-servant duo is represented by Colonel Henry Blake, a good surgeon but an ineffectual commander and bumbling administrator, and his myopic but capable clerk, ‘Radar’ O’Reilly. The comedy of a master-servant act nearly always arises from the fact that the servant, in all but social status, is superior to his master. Jeeves and Sam Weller, in their different ways, are perfect débrouillards: they excel at finding ways to do whatever the plot requires, to get their masters out of scrapes, and generally unknot all the knots that their ostensible betters have tied. Radar keeps the 4077th MASH running. At one point, the bemused Blake frankly asks him about the endless Army paperwork: ‘Do you understand any of this?’ Radar replies: ‘I try not to, sir. It slows up the work.’ Radar’s apparent powers of precognition keep him a step ahead of everyone else, but he is generally three steps ahead of Blake.

The star-crossed lovers of M*A*S*H, taken with little change from the movie, are the two majors, Frank Burns and Margaret ‘Hot Lips’ Houlihan. In Gelbart’s original conception, Frank Burns is taken over virtually unchanged from Altman’s version, but Hot Lips, besides being a hard-nosed Regular Army nurse and full-time martinet, is also a promiscuous man-eater with brass stars in her eyes. She has romanced, or at least towsed, a bewildering variety of colonels, generals, and at least one warrant officer, and Burns, who knows this, is transported into frothing fits of jealousy whenever a high-ranking visitor shows up at camp. (‘I could never love anyone who didn’t outrank me,’ says Hot Lips at one point, frankly giving the lie to her year-long affair with a mere major.) The idea that religion was necessarily hypocritical or stupid would not fly with the network censors in 1972, so Burns’s sanctimony is downplayed after the first few episodes, whilst Hot Lips becomes his equal partner in hypocrisy. In their very first appearance in the pilot, we see them sitting at a table together, he reading the Bible and she an Army manual, while under the table they are playing footsies.

The most radical change occurred with the surgeons in ‘The Swamp’ – named after the actual tent at the 8055th MASH where Richard Hornberger lived during his hitch in Korea. In the book and film, Duke Forrest, a stereotypical Southerner, and Hawkeye Pierce, a cut-up from small-town Maine, are eventually joined by Trapper John McIntyre, a chest cutter from Boston with a dry wit, a wide streak of irreverence, and superb medical qualifications. It is Trapper, in both the book and the movie, who is made Chief Surgeon in response to Frank Burns’s complaints about disorder in the O.R. Gelbart put all three surgeons’ DNA in a blender and used them to make his third and most important double act. Duke disappears; Trapper becomes a general surgeon, practical joker, and all-round cut-up; and Hawkeye, who was originally a stand-in for Hornberger himself, becomes the nosegay of all surgical virtues and the sump of all military vices. It is Hawkeye now, not Trapper, who is qualified in chest surgery and becomes Chief Surgeon, and Hawkeye who gets the best one-liners, with a pronounced tendency to develop into comic monologues (or very un-comic anti-war rants) as the series progresses.

The fourth denizen of the Swamp, in all three versions, was a black neurosurgeon, ‘Spearchucker’ Jones – the obvious racial slur being redeemed, in this instance, because Jones was an all-round athlete in college, not only a football player but a track star who specialized in the javelin. This is made explicit in the novel, alluded to in the movie, and left rather embarrassingly unmentioned in the series, in the short time before Jones was simply written out of the show. (This reduced the unit’s complement still further, to four surgeons including the C.O.) Various conflicting reasons have been offered why Spearchucker disappeared, but in fact he was simply unnecessary, and his character could not be developed without taking away necessary screen time from the other cast members. Duke Forrest would undoubtedly have suffered the same fate, if Gelbart had not had the artistic courage to cut him out from the beginning.

In the first season, the television series featured a number of minor characters, some carried over from the earlier versions, some original: ‘Ugly John’ the anaesthesiologist; General Hammond, Col. Blake’s superior at headquarters in Seoul; a corpsman named Boone; and a parcel of nurses including Blake’s love interest, Leslie Scorch, Hawkeye and Trapper’s occasional girlfriend, Lt. Cutler, and the ‘completely edible’ Lt. Dish. All these characters were written out of the series, at the network’s insistence, after the first season, except for the chaplain, Father Mulcahy, who eventually became a series regular. It is probably true that there were too many minor characters for a half-hour show; it could be rather a chore for a viewer to keep them all straight. I believe, however, that Gelbart was wise to include them. They gave a semblance of depth to the organization; they diffused some of the limelight away from Hawkeye and the other regulars, and made the 4077th seem more like a fully rounded hospital and less like a highly artificial stage show with a cast of six. These were important virtues, and in later years the show would suffer from their absence.

But it is the three double acts that carry the show for its first three seasons. Gelbart’s cast, supported by his writing and story-editing, was magic. All the crew had to do was put one of those pairs together on the screen, and the comedy happened of its own accord. It was hardly even necessary to write jokes; the humour arose naturally out of the relationships within each pair, and among the three of them. This is the finest and most natural kind of comedy writing. Left to themselves, those six characters could have carried on almost indefinitely; but they were not left to themselves. Gelbart’s M*A*S*H was torn apart by outside forces; but that is a story for another time.

With this post, I declare ye back in fine form! I grew up with the MASH TV show and loved it at the time – at least the early years. All TV shows, if long-lived, eventually jump the shark, and MASH leaped, not just jumped. However, as you state, the early years were glorious comedy indeed. I look forward to your next installment – I know nothing of the outside forces that ruined a fine show.

Thank you! It feels wonderful to have the monkey off my back, and know that I can still write coherently. The only comparable sense of relief I know of is the sight of the sign labelled GENTLEMEN after an hour of holding one’s bladder.

I’m glad to see that all of our discussions about this issue. and your studies, are bearing fruit in this series of essays.

But in the film, his character is combined with Major Hobson to produce Major Frank Burns, who is not only an adulterer and a quack, but a sanctimonious Bible-thumper. The blatant hypocrisy of his position makes him the obvious villain of the piece, at least until the point where he tries to beat Hawkeye to a pulp and is sent away in a straitjacket.

I always thought it was excessive to make Burns a bad surgeon as well as a bad human being.

Anyways, this was a remarkable write-up. I’m looking forward to the next post, as always.

In the movie, there is actually a justification for making Burns rotten in so many ways at once. As Duke Forrest says, ‘Every time a patient croaks on him, he says it’s God’s will or somebody else’s fault.’ The same deficiency of character is responsible for his failings both as a surgeon and as a human being.

In the TV series, of course, Burns is just a cartoon villain. It’s excessive, but it also drives the plots. I hope to have more to say about that later.

Alas, I find watching reruns of M*A*S*H almost unbearable now, despite enjoying it in ages past, due to the excessive use of the laugh track.

If you get hold of it on DVD, there’s an option that allows you to turn the laugh track off.

On “Par is a live patient”

My brother is a doctor, two tours in Iraq. He once told me his proudest accomplishment – “No one who came to me breathing, stopped.”

That is indeed an accomplishment to be proud of.

Very interesting. It’s been over three decades since I watched the show. I’ve been reluctant to call it up again via the wonders of the internet for fear it would fall apart since I was a teen all ignorant about either the Korean War or the perfidy of the anti-war movement of the 60s.

“Nowadays, after its century-long detour through the mass media, the serial story is having something of a revival…”

Especially among self-published authors in China, or so I’m told.

Interesting!

WOW, your essays are amazing. Half of this I got as a teenager watching the show, but your order, structure and tracework is masterful. (It helps to watch the eps in order, I imagine: I watched the first 4-5 seasons in semi-random syndication.) Kudos.