It is not bigotry to be certain we are right; but it is bigotry to be unable to imagine how we might possibly have gone wrong.

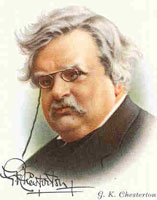

—G. K. Chesterton

G. K. C. on bigotry

G. K. C. on plain morals

There is one thing which, in the presence of average modern journalism, is perhaps worth saying in connection with such an idle matter as this. The morals of a matter like this are exactly like the morals of anything else; they are concerned with mutual contract, or with the rights of independent human lives. But the whole modern world, or at any rate the whole modern Press, has a perpetual and consuming terror of plain morals. Men always attempt to avoid condemning a thing upon merely moral grounds. If I beat my grandmother to death to-morrow in the middle of Battersea Park, you may be perfectly certain that people will say everything about it except the simple and fairly obvious fact that it is wrong.

Some will call it insane; that is, will accuse it of a deficiency of intelligence. This is not necessarily true at all. You could not tell whether the act was unintelligent or not unless you knew my grandmother.

Some will call it vulgar, disgusting, and the rest of it; that is, they will accuse it of a lack of manners. Perhaps it does show a lack of manners; but this is scarcely its most serious disadvantage.

Others will talk about the loathsome spectacle and the revolting scene; that is, they will accuse it of a deficiency of art, or æsthetic beauty. This again depends on the circumstances: in order to be quite certain that the appearance of the old lady has definitely deteriorated under the process of being beaten to death, it is necessary for the philosophical critic to be quite certain how ugly she was before.

Another school of thinkers will say that the action is lacking in efficiency: that it is an uneconomic waste of a good grandmother. But that could only depend on the value, which is again an individual matter.

The only real point that is worth mentioning is that the action is wicked, because your grandmother has a right not to be beaten to death. But of this simple moral explanation modern journalism has, as I say, a standing fear. It will call the action anything else—mad, bestial, vulgar, idiotic, rather than call it sinful.

—G. K. Chesterton, All Things Considered

[Paragraph breaks added — T. S.]

G. K. C.: ‘On Mr. Thomas Gray’ (excerpt)

Collected in All I Survey (1933).

A newspaper appeared with the news, which it seemed to regard as exciting and even alarming news, that Gray did not write the ‘Elegy in a Country Churchyard’ in the churchyard of Stoke Poges, but in some other country churchyard of the same sort in the same country. What effect the news will have on the particular type of American tourist who has chipped pieces off trees and tombstones, when he finds that the chips come from the wrong trees, or the wrong tombstones, I do not feel impelled to inquire. Nor, indeed, do I know whether the new theory is proved or not. Nor do I care whether the new theory is proved or not. What is most certainly proved, if it needed any proving, is the complete lack of imagination, in many journalists and archæologists, about how any poet writes any poem. [Read more…]

G. K. C.: Stories vs. literature

But people must have conversation, they must have houses, and they must have stories. The simple need for some kind of ideal world in which fictitious persons play an unhampered part is infinitely deeper and older than the rules of good art, and much more important. Every one of us in childhood has constructed such an invisible dramatis personae, but it never occurred to our nurses to correct the composition by careful comparison with Balzac. In the East the professional story-teller goes from village to village with a small carpet; and I wish sincerely that any one had the moral courage to spread that carpet and sit on it in Ludgate Circus. But it is not probable that all the tales of the carpet-bearer are little gems of original artistic workmanship.

Literature and fiction are two entirely different things. Literature is a luxury; fiction is a necessity. A work of art can hardly be too short, for its climax is its merit. A story can never be too long, for its conclusion is merely to be deplored, like the last halfpenny or the last pipelight. And so, while the increase of the artistic conscience tends in more ambitious works to brevity and impressionism, voluminous industry still marks the producer of the true romantic trash. There was no end to the ballads of Robin Hood; there is no end to the volumes about Dick Deadshot and the Avenging Nine. These two heroes are deliberately conceived as immortal.

—G. K. Chesterton, ‘A Defence Of Penny Dreadfuls’

G. K. C. on greatness in art

In the fin de siècle atmosphere every one was crying out that literature should be free from all causes and all ethical creeds. Art was to produce only exquisite workmanship, and it was especially the note of those days to demand brilliant plays and brilliant short stories. And when they got them, they got them from a couple of moralists. The best short stories were written by a man trying to preach Imperialism. The best plays were written by a man trying to preach Socialism. All the art of all the artists looked tiny and tedious beside the art which was a byproduct of propaganda. [Read more…]

Recent Comments