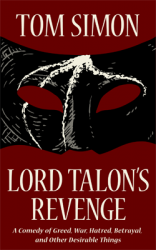

A man with no name, no country, no face, has one simple desire: revenge on the tyrant who robbed him of all else. Just a few small obstacles stand in his way. . . .

Greed: Sagrendus the Golden, Prince of Dragons, has a good business: abduct princess, collect ransom, repeat until rich. He charges extra for taking sides.

War: General Griffin, ogre mercenary, always fights for his client — even if there is nobody to fight against.

Hatred: Princess Jacinth hates the man she will have to marry — whoever he is. She also hates kings, rescuers, men, women, and especially porcelain dolls.

Betrayal: What keeps King Talvos on the throne of Ilberion? He’s better at double-crossing than anyone who double-crosses him.

And then there is one young fool with a sword, who still believes in heroes. Revenge is about to get a lot more complicated.

Now available from these fine ebook retailers:

Amazon.com

Amazon.co.uk

Amazon.ca

Kobo

Smashwords

Also on Apple iBooks. Check the iTunes Store or iBooks app for availability in your locality.

Chapter 1: How a Father sent forth his Son

Trianon Barr, like most fools, had the best of intentions. As a boy he sat by the fire in the hall of his father’s castle, away in the forgotten Kingdom of Lúmond, and listened to old tales. It was a rare night that some wandering bard did not sing for his supper at Castle Barr, playing airs on his harp before the lord’s table, or singing the ribald songs that delighted the rough knights of his household. But when the lord and his knights had retired, drunken and gorged, Trianon and his six brothers would beg the bard for tales of adventure and chivalry, and they would stay under the spell of his voice far into the night.

Trianon Barr, like most fools, had the best of intentions. As a boy he sat by the fire in the hall of his father’s castle, away in the forgotten Kingdom of Lúmond, and listened to old tales. It was a rare night that some wandering bard did not sing for his supper at Castle Barr, playing airs on his harp before the lord’s table, or singing the ribald songs that delighted the rough knights of his household. But when the lord and his knights had retired, drunken and gorged, Trianon and his six brothers would beg the bard for tales of adventure and chivalry, and they would stay under the spell of his voice far into the night.

So Trianon heard all the ancient lays that his elders never asked for, though they were the bard’s true psalter and treasury, the history of a letterless people. He heard of Garis the (Stupidly) Brave, who overcame the Dream-dragons of Northerland, and his bride Areia the (Tediously) Pure, who preserved their people from the demons of Rakennor. He was enraptured by the tale of Orsald the (‘Will I ever get to sleep?’ whined the bard) Everlasting, who routed the shadowy hordes of Sithron the Black in the war of the Old Gods. He thrilled to the epic of Old King Tal, who scoured the coastlands when the Old Gods were gone, and made there the fairest of all mortal kingdoms.

Worst of all, Trianon believed every word.

One by one his brothers left childish tales behind, and rode off to the stations their father found them. Trismegistus, the eldest, became a knight of the King’s household; the second became a Presbyter of the Green, the third a captain of cavalry, and so down the line. But Trianon kept listening to the bards even when he was made esquire to a petty lord of the Wyvern Marches; so that his head was fairly marinated in vain romantic notions, and his lord despaired of him at last. Then, having given him the accolade of knighthood by an exasperated wallop from a five-foot blade, he sent Trianon back in disgust to his father’s house. There the young knight had no one to tell him that the age of heroes was over, if indeed it had ever happened at all. He used to gallivant about the countryside on what he called errantry, and made an immortal nuisance of himself.

One day at the ragged end of winter, as Trianon rode knight-erranting on a stallion of some quality — it was a hand-me-down from his third brother, Trimontius, who was away at court flattering the best friend of the catamite of the confessor of the King, that being the proper way to get promoted in the cavalry — one day he heard, or thought he heard, a music of silver horns in the distance. The sound was most like the cry of a huntsman’s horn, but brighter and richer, its echoes laden with a sweet ache of enchantment. A fierce desire awoke in his heart, a desire to ride to far countries and brave unknown perils, to find the source of that music and make it his own, though it led him in chase to the ends of the earth.

Trianon reined in his mount. ‘Did you hear that, Zadek?’ he asked his manservant, a morose grey fellow twice his age, mounted on a morose grey donkey.

‘Begging your pardon, sir,’ said Zadek, patting his belly contritely. ‘It was cabbage and onions in the servants’ mess last night.’

Trianon gave him a bewildered look. ‘Cabbage and onions, Zadek? Fie on your prating! Horns I heard, horns of bright silver, that echoed from the utmost walls of yonder valley.’

Zadek gave Trianon a reproachful look, as nearly as one could tell through the fringe of silver hair half hiding his eyes. ‘Now, sir, there’s no call to mock. I was never so loud as all that.’

It occurred to Trianon that they were arguing at cross-purposes. Dismissing it with a shrug, he started his mount down the broad slope of the valley at an easy canter. The donkey’s short legs laboured to keep pace. Soon he had left behind the chill and stony hills of his father’s domain, and was riding through a low country of rich tilled plots and lush green pastures, divided by dry-stone walls. Away to his right a moor of brake and timothy sloped lazily up to a long, treeless ridge that bisected the valley. As he scanned the ridge for trumpeters, or at least for foes, he caught sight of a fair young damsel in a fairly obvious state of distress.

For the ridge ran through the lands of Lord Carle, who was a curmudgeon of the first water, and his son took after him; and this son, seeing a trespasser silhouetted on the crest, had set his hounds on her. Her mount, a high-strung palfrey, had balked at the dogs, and was rearing and skittering on the brink of a steep slope that fell away to a cold, pebbly stream. Trianon forgot all about horns or cabbages, as the case might be. His imagination leapt to a fevered state of attention.

‘Wolves, Zadek!’ he cried. ‘Dire wolves of the frozen North! They have driven that damsel to the brink of a mighty precipice. Come! We must ride to her rescue!’

Trianon dug his spurs into the charger’s flanks, and it responded like the blooded veteran it was: it charged. Before his brother Trimontius discovered the importance of catamites and their friends, he had wasted a lot of time on irrelevancies like leading men and fighting battles. A horse with that kind of experience cared not a fig for hounds. It bowled through them like a cannonball through ninepins and kept going. Trianon hauled hard on the reins until the charger subsided into a trot, and circled back to meet the palfrey on the second pass. The hounds forgathered to watch from a safe distance.

The girl was a fair rider, and had reined in her palfrey by the time Trianon reached her. ‘Fair lady,’ he said, ‘I fain would plight my horse and my sword to the service of your beauty.’ Or rather, he set out to say it; but he had hardly begun when his charger scented mare, and tried to express its own appreciation in a more direct and earthy manner. Between the earliness of the season and her ordeal with the hounds, to say nothing of riders and saddles, the mare was in no mood for a mating. It was only natural that she should neigh angrily and shy away. And as there was a sixty-degree slope behind, it was only natural that she should lose her footing and drop into the stream with a freezing splash.

By sheer luck, whether good or ill, Trianon had just taken the girl’s hand to bestow a courtly kiss upon it. When the palfrey fell from under her, he snatched her out of the air with the practised skill that clumsy people acquire by a lifetime of accidents, and set her down neatly on his saddlebow. Her hair was long and brown and windblown, her body lean rather than slender, in the way that horsy young women have; eyes blue and wide with shock, face flushed, bosom heaving, for so many successive jolts had left her rather winded. In short, she was thoroughly flustered, and she was the kind of girl who looks her best with a good fluster. Trianon was stunned by this vision, and when being stunned failed to express his feelings, he was forced to resort to speechlessness.

The girl disentangled herself from his nerveless grip and dropped easily to the ground. ‘Thanks awfully,’ she said, dusting herself off. ‘’Fraid Snowdrop is rather terrified of hounds. Were they yours?’

Before Trianon could answer, a booming voice broke in: ‘No, they’re mine! And if any harm’s come to ’em, I swear I’ll — Hul-lo!’

A burly young man had ridden up behind Trianon while he was gawping. A beefy right hand flew to the man’s sword-hilt, but before he could draw it, he rounded to and caught a glimpse of the brown-haired girl. ‘Hul-lo!’ he repeated, adding a low wolf-whistle for emphasis.

‘Your pardon, Lord!’ the girl said meekly.

The burly man grinned. ‘My father’s the lord, not I. Sir Braggan Carle, very much at your service, my lady.’ He dismounted and bowed low. ‘So sorry my hounds troubled you.’

‘Oh! It was nothing. Nothing at all. —Mariel Keldan,’ she said, sketching a curtsy. Trianon worked his jaw up and down like a small dog trying to take hold of a cow’s thighbone. By a supreme effort, he managed to emit a plaintive squeak.

Meanwhile Zadek came plodding up the hill, leading Snowdrop. The palfrey was chilled and winded, but not otherwise injured. ‘Your horse, ma’am,’ he said, pulling his silver forelock as he handed her the reins. ‘She’ll have a chill in her muscles, I shouldn’t wonder. I’d give her a good rub down if I were you.’

Sir Braggan Carle offered Mariel a musclebound arm. ‘It’s late,’ he said, ‘and your Snowdrop won’t bear hard riding after that fall. You’ll stay at my father’s castle tonight.’

‘Thank you!’ said Mariel, casting confused glances at her troop of benefactors. Sir Braggan led her away and helped her into the saddle behind him. By the time Trianon found his voice they were off at a slow trot, with Snowdrop trailing after.

‘Sir Trianon Barr,’ he said to the empty air. ‘At your service, my lady.’

Zadek gave him a mournful look through the silver tangle of his hair. ‘Let’s be off home, sir,’ he said. ‘I shouldn’t wonder if it snowed tonight.’

It did snow that night in the highlands of Barr, and for several nights after. Trianon spent the days moping by the hearth in his father’s hall, licking the wounds of his pride. The frost broke, the crocus bloomed, and Trianon remained inconsolable. The first earthworm squirmed through the half-frozen soil, raised its head into the bright clear air, drank in the sunlight and the sheer joy of a new lease of worm-life at the end of a hard winter, and disappeared ecstatically down the gullet of the first robin. Trianon thought it served him right.

But even the most assiduous moping cannot keep a young man’s spirits down for ever. The harsh winds of the thaw gave way to the generous warmth of full spring, and Trianon quit the hall to spend his days on horseback, straining his ears for some distant echo of the silver horns; but he did not hear them again. One day, despairing of horns, he thought he would settle for a glimpse of Mariel; so he rode down the valley to the edge of Lord Keldan’s lands. And there indeed he found her: the picture of demure beauty, clad all in white, studiously pretending not to notice her admirer. Unfortunately for Trianon, the admirer she was pretending not to notice was Sir Braggan Carle. She failed to notice Trianon without any pretending at all.

It was for Sir Braggan’s benefit that Mariel went riding nearly every day thereafter, picking primroses to set in her long dark tresses, singing sweet maidenly songs, and suchlike virginal wiles. If Trianon had been in the habit of observing the obvious, he might have noticed this. But he was far too busy being smitten.

Sadly, Sir Braggan was not in the habit of observing the obvious either. Had Mariel been a fine chestnut brood-mare or a well-built foxhound bitch, that would have been another matter. Not that he lacked all interest. Her dowry included some hundred acres of the best deer-park in Lúmond, and his father had begun haggling with Lord Keldan to arrange a match. But her personal charms had nothing to do with the case.

They had everything to do with Trianon’s case, however, and as the second full moon of spring approached, he decided to lay siege to the lady’s affections. ‘What think you, Zadek?’ he asked, dreamily watching as Mariel wove white flowers into a garland. ‘According to the bards, it would be proper to send word by the lady’s maidservant, telling of my undying devotion. You must bear my message thither.’

‘As you like, sir,’ said Zadek doubtfully. ‘Not that the young lady would take it kindly. Set her father’s dogs on us, I shouldn’t wonder.’

Trianon clapped Zadek on the back. ‘Stout fellow! The Lady Mariel loves flowers, as do all fair maidens, ’tis said. With mine own hand I shall pick a nosegay from some goodwife’s garden, as an earnest to accompany my words. You shall take them to — What is the maid’s name, Zadek?’

‘Gerda, sir.’

‘As you say. But all must be in secret. Have you some innocent cause to seek her company?’

Zadek had already been seeking Gerda’s company for a perfectly guilty cause, but he thought it wiser not to say so. ‘Hard to say, sir.’

‘Excellent! I shall gather blossoms — marigolds for Mariel, what say you?’

‘I don’t think they’re in season, sir.’

‘I care not. I shall gather blossoms, I say, and you shall bear them to Gerda, with my words for her mistress. Tell her to say unto the Lady Mariel—’ Trianon pursed his lips and thought hard. ‘Say that of all the birds of the air and the flowers of the field, there is none fair save by the grace of her favour. Say that the sun was dark and the wind was still until Mariel came to give them life. Say that in the day that she first came gathering posies in the bright mead, the winter of my heart ended, and all the world quickened to glorious spring. Say—’ He chewed his thumb pensively. ‘Say that her knight has beheld her from afar, and wishes only to worship in the temple of her presence. Have you got that, Zadek?’

‘Temple of her presence, ay, sir. Her knight, Sir Trianon—’

‘Nay, nay, Zadek! Speak not my name, not yet. Let her but know that she is admired — that she is desired. Let her delight in the mystery awhile. When the time is ripe, I shall declare myself.’

‘Very good, sir. Her knight, who hasn’t got a name, has beheld her from afar.’

‘Just so! Come to me at midday, and I shall give you the flowers. Keep them well hid, and let no man guess your errand.’

Gerda must have passed on both flowers and words to some effect, for when Mariel took her ride the next morning, she glowed with a smug and secret joy. She wore a diaphanous gown of apple green, a golden circlet in her hair, an enigmatic smile on her rosy lips, a delicate flush on her cheeks, artfully applied out of a jar. It was an effort well wasted. Sir Braggan, engrossed in the training of a promising young hound, paid her not the slightest heed. She withdrew in a frosty huff.

That evening, Trianon rode within bowshot of Lord Keldan’s castle, Zadek in tow. Picketing his horse at the roadside, he went on under cover of dusk. The stars were coming out when he reached the lawn under the outlying tower where Mariel sat in her chamber, working at a bit of embroidery by candlelight. Since the castle was built more for show than for defence, Mariel’s chamber had a proper window and a small but genuine balcony. To climb the ivied trellis and make off with her would have been the work of a moment for any resourceful rogue. Perhaps Lord Keldan had put his daughter there with just such a rogue in mind.

If that was his hope, it miscarried. While Trianon might pass for a rogue in a dim light, he was anything but resourceful. Craning his neck to see Mariel’s lithe form silhouetted in the window, he unslung a battered mandolin and spent a painfully long while tuning it. Zadek ground his teeth at the noise. When each string was individually and sublimely off key, Trianon began to plink out an air with fingers made clumsy by the nightly chill. The window opened briefly to disgorge an old boot, which he caught deftly in the eye. Nothing daunted, he started another tune: a fractured rendition of ‘Lily o’ the Moon,’ or perhaps a foul slander on ‘My Love’s a Rose with Many a Thorn.’ And to make his performance perfectly pathetic, he lifted up his voice in a foul imitation of song.

The hardest heart would have been moved by that unearthly noise, and Mariel’s heart was anything but hard. She stepped out onto the balcony, her body wrapped in a pale rose nightgown, her face bathed in moonlight, and cried out in a voice more melodious by far than her admirer’s: ‘Stop that noise or I’ll brain you!’ And she hove half a brick over the waist-high battlement, missing Zadek by inches.

Trianon left off torturing his mandolin. ‘O fair lady Mariel, it is I, your knight! I have come to—’

‘Oh, my sweet knight!’ Mariel’s voice was transformed with astonishment and delight. ‘Come up, come up this instant!’

Trianon started up the trellis, but lost his footing in the ivy and fell heavily to earth. The mandolin snapped under him with a mournful twang. ‘Are you all right, my love?’ asked Mariel, peering anxiously over the battlement.

‘I would fain take a thousand such falls, fair lady, to hear those words from your lips! Zadek, give me a hand up.’

‘As you wish, sir,’ came a muffled voice. Trianon started back up the trellis, his booted toes prodding for footholds. After a good deal of fumbling he found a handy ledge, a sort of round protrusion from which he could really launch himself into the climb.

‘You’re standing on my head, sir,’ said Zadek.

Trianon took his weight off his manservant and hauled himself up the wall, while Mariel carolled words of encouragement. ‘Sir Braggan!’ she cried warmly, stooping to kiss him.

‘Sir Trianon,’ he said as his pale face popped up in a crenel.

Mariel’s lips unpuckered. ‘Sir Who?’

‘Sir Trianon Barr. Your knight.’

Mariel clapped a snowy hand to her forehead. ‘Oh, you silly weed. What are you doing here?’

Trianon’s answer was lost in a sudden baying of hounds. Two human voices rose above the pack. One was Zadek’s, crying out as a dog sank its teeth into a sensitive part of his anatomy. The other was Lord Keldan’s scandalized shout: ‘Mariel! You have got a man on your trellis!’

‘Not as such, Father,’ she answered. ‘It’s that daft boy of Lord Barr’s.’

‘Is it now? Well, boy, if you don’t get off my wall in a pig’s whisper, I’ll put a spear in your back.’ Trianon let go and dropped, and might have broken a leg, but as luck would have it, Zadek was there to break his fall. ‘Now clear off,’ said Lord Keldan, ‘and leave my daughter alone.’

Two men-at-arms escorted Trianon back to Castle Barr and deposited him in the great hall, where his father sat glowering upon his high seat. ‘What do you have to say for yourself, boy?’ he shouted, and without stopping for an answer he went on: ‘It’s a year since you were knighted, you clot, and what have you done since then? Mooned about like a lovesick calf, and stuck your foul nose into all the neighbours’ business. Errantry, bah!’

‘My lord and father,’ Trianon replied earnestly, ‘it is dole and sorrow to me that I have done no deeds of worth to add to the glory of the House of Barr. But I have not passed all my days in idlesse. Peradventure—’

‘Stop that! I’ll have none of that high language in my castle. If you’ll not curse and mumble like a proper Lúmondish knight. . . .’ Lord Barr trailed off, unable to think of a suitable threat. ‘Oh, get to the point. And it had better be good.’

A faraway look came into Trianon’s eyes, making him seem enraptured, or perhaps just unusually stupid. ‘But few days since, when spring first touched the lower meads, I heard as it were a music of distant horns, a voice of valiant trumps calling to me across the abysm of ages. I yearn to follow that voice. I would fain walk in the footsteps of Orsald or Tal, and see what name I might make for myself in the world. I wish to be a hero, my lord.’

‘A hero?’ the old man roared. ‘Am I a hero, that my son should be one also? People would think you were illegitimate. By thunder, I’ll not have it!’ He crashed his right fist down on the arm of his chair. ‘Now be off with you, before I lose my temper!’

Trianon bowed and withdrew. Zadek made to follow him, but Lord Barr checked him with a gesture. ‘Not you, churl.’

Zadek pulled his forelock. ‘As you wish, my lord.’

‘It looks to me like Trianon’s wits have finally slipped their leash.’

‘I shouldn’t wonder, my lord.’

Trianon’s father sighed. ‘Where did I go wrong, Zadek? What have I done to deserve him?’

Zadek regarded him mournfully through his curtain of silver hair. ‘You do have six other sons, my lord.’

Lord Barr brightened. ‘That’s true. But by my beard, I thought seventh sons were supposed to be lucky.’

‘Fool’s luck, my lord, if you ask me.’

‘Hah. Much good it may do him. Damn his lights and liver, what am I going to do with him? If only he’d gone bad in a normal way, like Triskelion. Wining and wenching would make less talk than — than this rot. Trumps indeed!’

Zadek licked his lips and said in a tentative murmur: ‘By your leave, my lord?’

Lord Barr looked down at him with a flinty eye. ‘Well?’

‘I’m a poor man, my lord, too poor to marry or sire a child—’

‘If it’s money you want, the answer is still no.’

‘—but I have had a father, and I know how a father cares for his sons. I shouldn’t wonder if you had my neck in a noose, for what I’m about to say may be Trianon’s death.’

‘We can always hope,’ said Lord Barr drily. ‘Keep talking.’

‘My lord, Trianon is a troublesome lad, though spirited—’

‘Troublesome is not the word, Zadek. He’s a freak of nature! Serenading Lord Keldan’s daughter! I ask you!’

‘Perhaps he has a sensitive soul.’

‘He’ll have a sensitive hide when I’m finished with him! He’s made me a laughingstock for the last time. If that nitwit Tulf hadn’t knighted the brat, I’d lock him up. Or hire him out to a village that wants an idiot. But you can’t do that sort of thing to a knight.’

‘My lord, you could let him be a hero.’

Lord Barr stared as if Zadek had just laid an ostrich egg. ‘Let him be a hero? As well let him fly to the moon. By thunder, do you think me a bigger fool than he is?’

Zadek cringed and wrung his hands. ‘I meant no offence, my lord! What I mean is this. Let him chase his dreams. Give him a fast horse and point his nose west. He’ll go questing in the mountains, and with any luck, he won’t come back.’

A smile spread across Lord Barr’s face like a snake sunning itself on a warm rock. ‘By thunder, Zadek, that is an idea. He can chase his imaginary trumpets clear off the cliffs at the world’s end. It’ll have to be two horses, but that’s a small price to pay. Wonderful! You’re a marvel, Zadek. I hate to think how I’ll get by without you.’

Zadek swallowed hard. ‘Without me, my lord?’

Lord Barr hopped down from his high seat and gave Zadek a friendly clap on the shoulder. ‘Come, come! My heart is not so hard. Trianon needs a keeper; I know that as well as you. I can’t turn him out in the wild alone. He might be eaten by bears — or burnt up by dragons — or worse yet. . . .’

‘My lord?’

‘He might even come back. You will try to prevent that, won’t you, Zadek? Because if ever you set foot on my lands again, I’ll have you hanged as a horse-thief.’

I enjoyed Lord Talon’s revenge very much and I left an opinion in Amazon.es (being a writer myself, I wish more people would do that after reading a book). I’ll reproduce it here:

Well-written fantasy tale. The style reminded me a little of Terry Pratchett’s. It’s witty and fast-paced. The characters are likeable.

I just wish the female characters had been a little more virtuous (in the old Victorian sense of the word) and the end of the dragon had been a bit more spectacular. Other than that, a very good book.

I’ve just started it and am enjoying it immensely. I’ll let you know when I get a review posted. I second the Terry Pratchett whiff (but that’s a good thing).

I’ve left you a glowing review on Amazon and Goodreads. I about choked on my drink when I came across the Modern Major General tribute.

Now if only you could get Frank C Pape illustrations to go along with it. The women were straight out of James Branch Cabell, slightly updated.

This is a wonderfully fun and great read. I feel, somehow, that I’ve lived this in a way…

I am recommending this to all that I know will appreciate it.