In a discussion at The Passive Voice, Karen Myers wrote at considerable length on the differences between the so-called prestige dialects of written English and other languages, and the colloquial dialects that make up the spoken languages. She ended with this bit of advice:

If you want to write an essay, use formal written English. If you want to write a narrative, use voice (the spoken language in all its registers).

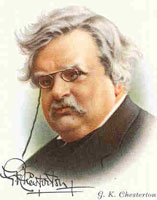

Being the ancient curmudgeon that I am, I had to demur. And being the lazy curmudgeon that I am, I had to cut and paste and repost my response here, as a trifle of evidence that I have not gone entirely silent. Here is what I had to say:

The key, which hardly any linguists seem to have grasped, is that formal English is rhetorical and colloquial English is conversational. Nearly all the differences between them can be explained in terms of information theory.

(Referring again to ancient history: when I was a linguistics undergrad, information theory was not offered even as an option as part of the curriculum. It was a third-year maths course open, I believe, only to maths majors. My professors not only didn’t know it, they didn’t know it had any applicability to languages, and some of them, I believe, had never heard of it at all.)

In terms of information theory, the strict grammar and finely graduated vocabulary of formal English are error-correction devices. When you converse with another person or a small group, your listeners can give you immediate feedback, and if it appears that they did not understand you according to your intentions, you can immediately offer an explanation or a rewording. You can’t do this in either a published text or a speech to a large crowd. You therefore have to include such cues in the text as are needful to avoid ambiguity and misunderstanding. The art of rhetoric is not concerned only with swaying people’s emotions, as some people suppose; it is also about expressing your case with force and clarity when close two-way communication is not practicable.

This is a difficult art, and those who teach it are rewarded by being called ‘prescriptivists’, who, as any Postmodernist linguist can tell you, are the source of all evil in the universe. One of my professors told me flatly that all prescriptive statements about usage and grammar are by definition wrong; whereupon I concluded that she knew nothing about her subject and transferred to a different class.

The linguists of the anti-prescriptivist school claim that there is no such thing as an error in usage, that whatever any native speaker of a language says is automatically valid and grammatical. But they do not hesitate to use asterisks to indicate erroneous constructions: *goed, *childs, *gooses, and the like. What they object to is that people who know formal language should presume to teach it to those who only know the language in its colloquial registers. They believe that status-signalling is the only reason why formal language exists, and flatly refuse to ask how or why a given dialect came to be associated with high status in the first place.

In the cases of English and German, the formal language was codified chiefly in response to the need to translate the Bible, which is a notoriously difficult text. Luther in German, Tyndale and the Douay-Reims and King James translators in English, had to invent numerous idioms and turns of phrase to accurately convey the meaning of the original in a vernacular edition. And they had to do it in rhetorical, not conversational, language, because their translations would be read by multitudes of people who could not ask the translators for clarification, and they would be read from the pulpit to large crowds of people who could not even request clarification from the preacher. They had to solve the technical problem of error-correction for their translations to be useful at all. (Other translators tried and failed, or succeeded to a lesser extent, and their efforts are forgotten except by specialist scholars.)

A number of languages achieved their first literary form in this way. The principal surviving text in Gothic, for instance, is a large fragment of the Bible as translated by Wulfila (or a committee which he is believed to have led; cf. paintings by the ‘School of Rembrandt’). Several North American aboriginal languages were first committed to writing in the same way and for the same reason. In each case, the dialect employed in the translation became a standard reference point for the later literary use of the language, not because kings and princes favoured it, but because the Christian part of the population were familiar with their vernacular Bible, heard it weekly, often quoted it daily, and there was no other uniform published text which similarly large numbers of people could be expected to know well.

The Latinate garbage which was grafted onto formal English in the eighteenth century – the shibboleths about prepositions and infinitives and so forth (which I agree with you in despising) – was the product of a time when highly educated Englishmen were expected to be learned in Latin, and English gentlemen were expected to pay lip service to Christianity without actually believing it. To these people, the prestigious author par excellence was Cicero, and you can see exactly how they tried to remodel English to resemble his pompous and artificial Latin. But that attempt did not ‘take’ in the long run, because unlike the Bible, the works of Cicero were of no interest at all to the bulk of the literate populace. The professors worshipped Cicero, the schoolmasters assigned him, the upper-class schoolboys were bored by him, and the classes below them didn’t care a fig about him if they had heard of him at all.

In light of all this, I would modify your closing advice: If you want to write a narrative, use written (i.e. rhetorical or error-correcting) English – but disguise it with the idioms of whatever colloquial speech is appropriate. Part of the art of rhetoric, after all, is to plausibly deny that one is being rhetorical. Shakespeare knew this perfectly well, which is why he made Mark Antony say:

I am no orator, as Brutus is,

But, as you know me all, a plain blunt man

That love my friend, and that they know full well

That gave me public leave to speak of him.

For I have neither wit, nor words, nor worth,

Action, nor utterance, nor the power of speech

To stir men’s blood. I only speak right on.

Addendum. I do not know of any finer or pithier example of a man using rhetorical English, and even as he does, pretending that he is ‘just plain folks’ talking colloquially.

Recent Comments