Jonathan Moeller has tagged me for The Next Big Thing. I am nearly as susceptible as a dragon to flattery (although, unlike Smaug, I am painfully aware of the weak points in my armour); what is more important, I am stuck on the all-important cover copy for the Octopus, so I can answer these questions as a sort of rehearsal. [Read more…]

Conservatives, progressives, and educational methods

First the text, from the immortal Chesterton:

The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of Conservatives is to prevent mistakes from being corrected. Even when the revolutionist might himself repent of his revolution, the traditionalist is already defending it as part of his tradition. Thus we have two great types — the advanced person who rushes us into ruin, and the retrospective person who admires the ruins. He admires them especially by moonlight, not to say moonshine.

And now the sermon. This is from ‘docargent’, a commenter on Sarah A. Hoyt’s blog. I offer it with the caveat that the teacher cited cannot be reached to confirm the story:

I worked as support staff in a middle school once and, having been left almost innumerate due to the New Math, asked a teacher nearing retirement if anything done since the New Math had worked as well as the methods used before it. When she said no, I asked why public schools never went back to the pre- New Math method.

“There’s no money in it,” she said.

According to her, school districts receive federal grants to use new and experimental teaching plans. If these fail, and they usually do, no effort is made to correct the damage done to the education of the students used as guinea pigs; they’ll have to pick the subject up themselves later on. The school districts need the grants to pay for various unfunded mandates.

I thought this over and asked her if this meant that if an experimental teaching method did actually work, the district would still abandon it in a few years for something totally untried in order to get a new grant.

“Yes,” she said.

In for a penny, in for a pound

It comes to my notice that silver bullion, after trading a bit lower for several months, has just rallied above $32 per troy ounce (London fix), or £20 per ounce in sterling. This figure has a sad historical significance.

In the Middle Ages, the values of English coins were legally defined in terms of Tower weight. This system of measures was nearly identical to the modern troy units: the ounce and pound were the same, but the size of the grain, and the number of grains per ounce, were different. (Tower grains are sometimes called ‘wheat grains’, and troy grains are called ‘barleycorns’, to reflect this difference.) The same units, with one annoying variation, were used to denominate and to weigh silver coin.

The pound sterling — £1 — originally equalled one Tower pound of sterling silver; it was divided into 20 shillings of 12 pence each, making 240 pence to the pound. Just to make things difficult (for what would English measures be, if they were rational?) the Tower pound was divided into 12 ounces of 20 pennyweight each. Therefore one penny contained exactly one pennyweight of sterling silver, but a shilling was only three-fifths of an ounce.

Let us ignore the difference between sterling silver (92.5% silver by weight) and fine silver (99.9%). Pure silver is too soft to use in coinage or much of anything else. Alloying it with 7.5% copper made it hard enough to withstand daily wear and tear, and also provided a small profit to pay the expenses of minting. We can consider a mediaeval English penny, including the cost of coining it, of effectively equal value to a pennyweight of pure silver. It is, as they say (in this case literally), ‘close enough for government’.

Today, as I have said, the price of silver crossed above £20 per troy ounce, or £1 per pennyweight. A so-called pound sterling today buys you as much silver as went into a single penny in the Middle Ages. It then follows that the pound has been devalued by a factor of 240 to 1, compared with its original valuation. And it also follows — and this is the sad historical significance — that the old saying, ‘In for a penny, in for a pound,’ has become a tautology — for a pound and a penny are now the same. (I do not speak of the decimalized ‘New Penny’, which is not a coin but a joke.) ‘Dollars to doughnuts’ is also beginning to express an equality, rather than long odds in the dollar’s favour. We shall have to invent some new idioms. And for that we can thank the rascally debasers of silver coin, and the mad printers of fiat money — that is, all our politicians for the last 500 years. I hope they would at least say, ‘You’re welcome.’

On bureaucracy

In another forum, on which a commenter offered an impassioned defence of bureaucracy, I countered with this:

In practice, bureaucracy is a way for petty officials to take the lemon of the rule of law, and turn it into the lemonade of the rule of men. This they do by making the rules so vexatious and difficult to obey that nothing can be done except by circumventing them through influence.

There is, or was, an office in Paris which is the sole source of a certain permit required to do a certain kind of business. In order to apply for this permit, you must have a properly filled-out form, obtainable from another office. The office that issues the form is only open in the afternoon. The office that issues the permit is only open in the morning. And the form itself is only valid on the date of issue. If you get the form on Monday afternoon, you cannot take it to the permit office until Tuesday morning, by which time it has expired. There is literally no way to obtain the permit, except by bribing the officials, or by being so rich and powerful that they dare not refuse you.

That, Sir, is why most people hate bureaucracy.

Templates

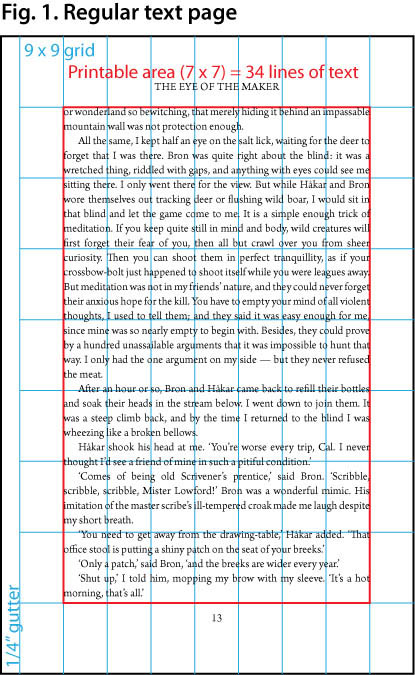

I’m in night mode right now, which is probably a good thing, since the Calgary Stampede has started up, and the drunken revelry down the hill from me doesn’t even begin to quiet down until 3 a.m. Fortunately I like working at night, and I’ve got a fair amount done this weekend: a CreateSpace template, an ebook template, and a lot of boning up on the art and science of book design. I give the details of my process here, in case anyone is interested.

The cry of the highbrow

‘Ah, Shakespeare. Quite a promising poet in a minor way, when he was writing those sonnets and sucking up to Queen Elizabeth’s courtiers. All very proper. Pity he squandered his talents by going into that low-brow theatre business.

‘I wonder what ever became of him? He could have been somebody if he’d stuck to proper literature.’

Publishing: self, trad, and the gross

One reads a lot about the different percentages that writers receive through self-publishing vs. traditional print publishing: for instance, this piece in Forbes about Mark Coker and Smashwords. I prefer to break down the numbers in a different way, by looking at grosses rather than percentages. With your gracious permission:

If I, as an unknown writer, do somehow sell a book to a traditional publisher, I’ll probably receive a $5,000 advance, take it or leave it, with no significant prospect of its ever earning out. So how much do readers have to fork over at retail to earn me that money?

In MMPB from a traditional publisher, I’m getting 8 percent if I’m lucky (assuming that sales and returns are reported honestly); lower rates from some houses. That means that readers have to spend $62,500 for me to earn that $5,000; which equates to 7,822 copies of a $7.99 paperback.

With a self-published ebook, I’m getting 60 percent on sales through an aggregator; more than that on direct sales through Amazon, but a bit of that will be lost to their bandwidth charge, so we’ll simplify the math and assume 60 percent across the board. I’ll need $8,333.33 in retail sales to earn my $5,000 nut. If I’m charging $3.99 for that book, I need to sell 2,089 copies.

I make the same amount of money from a quarter of the number of readers, and charging half the price. It’s a lot easier to find buyers for 2,000 widgets at $3.99 than for 8,000 widgets at $7.99. Of course books are not widgets; but different cheap editions of the same book are essentially fungible.

Looked at another way: if the reading public spends a million dollars on traditional print books, it provides a living wage for approximately two full-time writers. If it spends a million dollars on self-published ebooks, it provides the same wage for 15 writers. Gee, I wonder which is better for the writer.

The drudge and the architect

Some hours ago the idea of this essai came to me, hard and clear, demanding to be written, and proposing for itself the title, ‘Hard Work vs. Working Hard’. ‘Always,’ said Kipling, ‘in our trade, look a gift horse at both ends and in the middle. He may throw you’: therefore I did a quick search, and found another essay with that exact title, written barely four months ago, by one Scott McGrath. What he has to say is good, and valid, and useful, and I propose to take it as a starting-point; but his essay is general in application, and I want to apply the distinction particularly to the business of writing. So I have changed my title to ‘The Drudge and the Architect’, for reasons I mean to make clear later. [Read more…]

Procol Harum and G. K. C.

Thus, if one asked an ordinary intelligent man, on the spur of the moment, ‘Why do you prefer civilization to savagery?’ he would look wildly round at object after object, and would only be able to answer vaguely, ‘Why, there is that bookcase… and the coals in the coal-scuttle… and pianos… and policemen.’ The whole case for civilization is that the case for it is complex. It has done so many things. But that very multiplicity of proof which ought to make reply overwhelming makes reply impossible.

—G. K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

My Muse is actually an imp, or perhaps a pooka, and cannot read a passage such as this without taking it as a challenge. I shall accordingly give my reason for preferring civilization, in the form of an example; and I hope to show that the example I give would be utterly impossible except in a state of civilization, and indeed, inconceivable in any civilization but our own. Mr. Chesterton would doubtless be glad to hear that my example does at least include a piano. [Read more…]

Recent Comments