In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

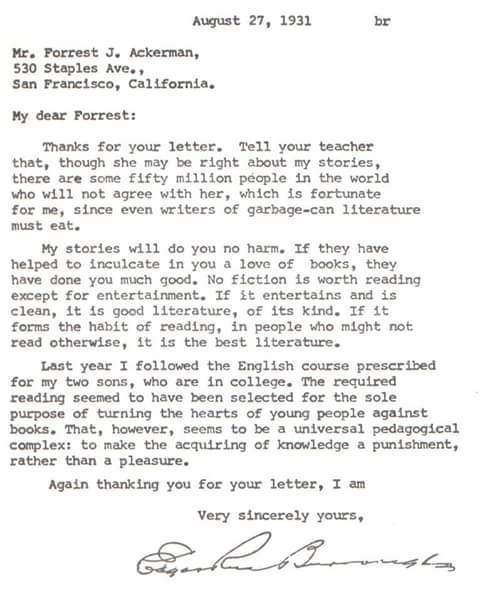

John McCrae was a physician and occasional poet from Guelph, Ontario. Upon the outbreak of the Great War, he was called to the colours under which he had served, and despatched to Belgium with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. As brigade surgeon to the 1st Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery, he treated the wounded under fire during the Second Battle of Ypres in April and May, 1915. During the intervals of the battle, he wrote the rondeau above, which was published anonymously in Punch that December and immediately became world-famous.

In every war before the advent of antibiotics, and a good many wars since, disease was a greater killer than enemy fire. Lieutenant Colonel McCrae (he had been promoted from major during the war) died of pneumonia and complications in January, 1918, ten months before the armistice. He was one of 60,000 Canadians killed in the First World War, out of a population of only eight million.

We still remember. God save us all from breaking faith with those who died.

Recent Comments